Warfare is like a deadly Super Bowl of Geopolitics, a match that includes violence, threats, boasts, trash talk, and posturing by quarterbacks designed to wither opponents. But during Russia’s war against Ukraine and Europe, the Kremlin has been tossing around nuclear threats and words like Armageddon in order to frighten off Ukraine and its Western allies. So far such fear-mongering has backfired. Ukraine has become more resolved. Loose talk about nukes has rattled the Russian public, resulting in the departure of one million from Russia since the invasion. In the United States, a survey by the American Psychological Association found that 70 percent were worried about nuclear confrontation and the possibility of World War III, but another poll showed that 75 percent of Americans support military help to Ukraine. Moscow’s threats have also alienated “friendly” fence-sitters like China and India and resulted in fierce pushback by Western leaders who are more determined than ever to stop Putin’s war.

Russia began nuclear “signalling” right after its invasion in February by announcing it had placed its nuclear forces on high alert to keep NATO forces from entering the fray. Weeks later, Putin’s attempt to capture Kyiv was repelled, and Russia pivoted to the east and south. By June, it controlled nearly 20 percent of Ukraine’s land mass, up from the 7.5 percent occupied in 2014, but Ukraine roared back, thanks to weaponry and funds from the US and its NATO allies. Since then, Kyiv has clawed back 5 to 7 percent of its territory, and continues to batter Russia’s increasingly demoralized armed forces.

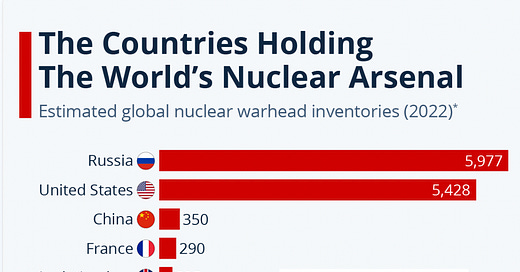

This counter-offensive, and the discovery of Russian war crimes, led to another veiled nuclear threat. On July 6, Putin’s sidekick, and potential successor, Dmitri Medvedev, warned against any attempt by the International Criminal Court to punish Moscow for alleged crimes in Ukraine. “The idea to punish a country that has the largest nuclear arsenal is absurd in and of itself," he wrote on messaging app Telegram, "and potentially creates a threat to the existence of mankind." In August, he issued another, after Russians occupied a major nuclear plant in Zaporizhzhia, by referring obliquely to “possible events” at nuclear plants. “The Horsemen of the Apocalypse are already on their way," he said.

This alarmed the United Nations and by September 1 the International Atomic Energy Agency arrived to monitor all activities at the nuclear plant. But as Russia remained bogged down in summer months, speculation surfaced that Putin may deploy tactical, or smaller, nuclear bombs to stop the Ukrainians. Putin stoked the nuclear threat by saying that any attack on Russia itself would be met with “any” means available and that he wasn’t bluffing.

At this point, President Joe Biden waded into the nuclear conversation to warn against the use of smaller, or tactical, nukes. “We’ve got a guy I know fairly well,” he said. “He [Putin] is not joking when he talks about potential use of tactical nuclear weapons or biological and chemical weapons, because his military is, you might say, significantly underperforming. I don't think there's any such thing as the ability to easily use tactical nuclear weapons and not end up with Armageddon.”

On September 21, Putin escalated the war, but in a non-nuclear way, by announcing the mobilization of another 300,000 troops. He also replaced military leadership in Ukraine with a guy nicknamed “General Armageddon”. These moves, and military intelligence, indicate that Moscow has played the nuclear card merely to frighten off opponents. There are no indications that the Russian military is readying deployment of nuclear weapons of any kind in any location, even after the Ukrainians tested Putin’s red lines by sabotaging Putin’s prize infrastructure, the $4-billion Kerch Bridge, linking mainland Russia to Crimea. Putin retaliated by unleashing dozens of missiles against civilian and energy infrastructure targets in Ukrainian cities. But none were weapons of mass destruction.

However, nuclear rhetoric continues. On October 12, former National Security advisor John Bolton said on a British TV show: “We need to make clear if Putin were to order the use of a tactical nuclear weapon he would be signing a suicide note," Bolton said. "I think that's what it may take to deter him if he gets into extreme circumstances…You can ask Qassem Soleimani in Iran what happens when we decide somebody is a threat to the U.S.," he said, referring to the Iranian military commander who was killed in 2020 by a U.S. airstrike in Iraq.”

The next day, on October 13, European Union foreign policy chief Josep Borrell warned Moscow that its forces would be “annihilated” by the West if Putin used nuclear weapons against Ukraine. “Putin is saying he’s not bluffing. Well, he cannot afford bluffing, and it has to be clear that the people supporting Ukraine and the European Union and the member states, and the United States and NATO are not bluffing either,” he said. “Any attack against Ukraine will create an answer, not a nuclear answer, but such a powerful answer from the military side that the Russian Army will be annihilated.”

The same day France’s President Emmanuel Macron clarified that Paris, one of three NATO nuclear powers, would “evidently” not use nuclear weapons in response to a Russian nuclear attack on Ukraine, but only if France itself was nuked. It was a nuanced remark, criticized by many, but probably designed so Macron could act as a backchannel to get Putin to negotiate a solution.

Shortly afterward, Biden held out hope for negotiations at a press conference by saying that “for the first time since the Cuban missile crisis, we have the threat of a nuclear weapon if in fact things continue down the path they are going. We are trying to figure out what is Putin’s off-ramp? Where does he find a way out? Where does he find himself where he does not only lose face but significant power?”

The next day, on October 14, Putin’s patsy – Belarus President Alexandre Lukashenko (who handed over Belarus to him two years ago) – articulated a nuclear climbdown, likely on behalf of Putin. In an interview with NBC Television, he played down the danger of nuclear war, but said that Putin should not be backed into a corner. He added that the West should not cross red lines (attacking Russia itself) and that Putin doesn’t need to use nuclear weapons because he has more than enough firepower to defeat Ukraine. He also announced that Belarus, despite hosting Russian troops and weaponry, won’t invade Ukraine. That same day, Putin announced that there was no need for more massive strikes on Ukraine and that he does not intend to destroy the country — a strange combination of tough action followed by an olive branch.

It’s obvious that Russian “Armageddon-ism” hasn’t worked. The West’s resolve and Ukraine’s army have strengthened and Putin now pins his hopes on flooding the battlefield with 300,000 reluctant recruits to turn the tide, not nukes. Hopefully, the war remains a clash between traditional armies and, if so, will end in victory for Ukraine, negotiations, or Putin’s departure … and not Armageddon.

I like the idea of the US diverting all missiles, air defence, all armaments to Ukraine that normally would be sent to Saudi Arabia as pushback against Saudi’s and MBS’s cutback of oil production.

It’s a perfect fit.

In a war people bleed, bones get crushed, and often die a painful death. It is by no means glamorous except for the vicarious wannabe. Being eliminated by fire, lead, or nuked still probably means a painful blood gushing finale.

Fighting furiously hard helps your survival, provided you know how to. It also shortens the drama.

Anyone who is willing to defend their country, even though their body may end up broken, rotting, and left for the birds to eat without leaving a memory of them - is a bona fide hero. M or F.

We may all find ourselves involved in a war if we cannot find better leaders.