In May, the island-nation of Sri Lanka off India’s coast with a population of 21 million defaulted on its debts for the first time in history after years of mismanagement. Its borrowings – made worse as a result of global inflation caused by Russia’s war – turned into a full-blown political and humanitarian crisis. In July, mobs looted and burned the Presidential mansion and surrounded parliament, enraged at shortages of fuel, food, medicines, and rolling energy blackouts. Leaderless for months, an interim government finally signed a preliminary bailout deal with the International Monetary Fund. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka is the proverbial canary in the coal mine. A “debt bomb”, involving more than 40 countries at risk of default, looms over the global economy and on September 15 the World Bank warned there will be a global recession this year.

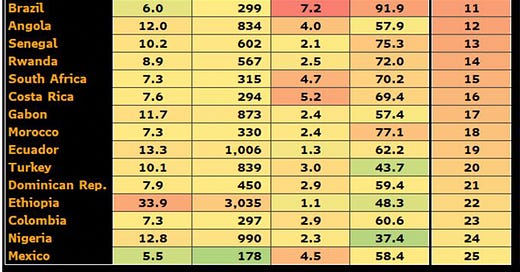

There are too many Sri Lankas around the globe, thanks to China and also to monetary policies in rich countries that unleashed a flood of cheap funds that were invested in or loaned to poor countries. Russia’s war this year adds to their burden by inflating the cost of food and energy for all nations, but hits the disadvantaged ones especially hard. The 19 emerging markets (in the above table) that are most at risk of defaulting on their sovereign debt has doubled since the Russian War began and represents more than 900 million people. Sri Lanka and Lebanon are already in default but others – notably Pakistan with a nuclear arsenal – are experiencing fiscal hardships that have also sent its people onto the streets in protest. Pakistan feverishly negotiates a bailout with the International Monetary Fund, and its stability is a priority, but more basket cases join the queue for rescue, including war torn Ukraine which needs $65 billion a year in non-military financing to keep the lights on as it wages war.

“There are more Sri Lankas on the way. You have countries like Myanmar, Laos. These are not major players in global markets, but they are falling," said the World Bank’s Chief Economist Carmen Reinhart in an interview with Reuters. She said others, such as Ghana and Egypt, were facing significant shocks as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine and surging food and energy prices. "There are a lot of countries in precarious situations,” she said.

Developed nations have escaped relatively unscathed for a while (except for Russia’s victims in Europe), but as defaults increase some banks will post huge losses, and global economic growth and global debt markets will take a hit. China also has its own debt crises, due to its real estate bubble domestically and over-investment abroad through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The danger is that this global over-indebtedness may lead to contagion and a major economic crisis for many nations that could take years to unwind. Such a “domino effect” of defaults is riskier than before, due to the interdependency as a result of the globalization of everything from supply chains to commodities, stocks, bonds and banking.

Plentiful cash from central bank printing presses drove down interest rates for years which enticed governments in emerging economies to borrow. The result is that their loans have increased to 67 per cent of their GDP on average, up from 52 per cent before the pandemic. Private sector players and citizens did the same, adding $5.8 trillion in debt in 2021, according to the Institute of International Finance. Now interest rates rise, along with the value of the U.S. dollars which they borrowed, making repayment impossible for many.

While war and easy money are contributing factors, the blame also lies with local government mismanagement, corruption, and China’s $1-trillion Belt and Road Initiative. This mega-project has been aimed at building infrastructure for poor, but geographically strategic, countries like Sri Lanka and dozens more.

China has spent billions building ports, railways, roads, and telecommunications facilities that were of strategic long-term benefit to its trade and political ambitions but often unaffordable for their country clients. China’s massive BRI was launched in 2013 by China’s President Xi Jinping and designed to enhance trade and influence. Many projects were not creditworthy, but politically expedient or ill-advised. Contracts and terms were incomprehensible or secret. Some critics maintain they were often “debt traps” set by Beijing to give credit to countries that could not pay back, enabling China to repossess plum assets. For instance, a Sri Lanka port project, built for $1 billion, had to be taken over by Chinese interests because payments on loans were impossible.

Another targeted nation was Malaysia which entered into a number of mega-project contracts with China in 2016. These received great fanfare and included a gas pipeline, a luxury real estate development, and various railways. But scandals erupted because kleptocrats profited from these and other initiatives and the biggest were suspended or cancelled, or left to languish, worsening its already unstable political and economic situation. Tunisia, Egypt, Kenya, and Argentina were all courted and now groan under piles of debt to China as well as Western bondholders.

According to a 2021 report from the College of William and Mary, 44 countries owed debt to China equivalent to 10 percent or more of their GDP, with some owing more than a quarter of GDP. China is the single largest lender to Zambia, which defaulted on its sovereign debt in 2020, and is currently undergoing debt relief negotiations.

China’s aggressive lending strategy has contributed mightily to the growing debt crisis, said German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and USAID head Samantha Power at a recent conference in India. Power blamed China for Sri Lanka’s crisis and was “an increasingly eager creditor of Sri Lankan governments since the mid-2000s.” She added: “Now that economic conditions have soured, Beijing has promised lines of credit and emergency loans … but calls to provide more significant relief have gone unanswered, and the biggest question of all is whether Beijing will restructure debt to the same extent as other bilateral creditors.”

The IMF and Western nations insist that China fully participate in restructuring the debts of these nations in equal measure. The World Bank’s Chief Economist Carmen Reinhart said the Common Framework for debt treatments agreed to by the Group of 20 major economies and the Paris Club of official creditors in October 2020 has been a disappointment, resulting in not even a single debt restructuring. “The historical experience has been like pulling teeth, and slow moving at that," she said. “Every creditor has for their own reasons engaged in foot dragging. China and private creditors have their own incentives to delay.”

The IMF has been tracking some 73 highly indebted nations and estimates that roughly 40 of these are at high risk of what it calls debt distress: In other words, they are either actively trying to restructure their debts, preparing to do so or already falling behind on their interest payments. And China has its own “Ticking Time Bomb” of debt I wrote about on August 25 equivalent to 275 per cent of its GDP because of its BRI loans as well as a speculative real estate bubble.

“This ain’t going away quickly. Everyone is preoccupied with their own problems. There’s a tendency to focus on the domestic issues and everything else goes on the back burner," said Reinhart. “I hate to be like a wet rag, but I do think things will get worse before they get better. We’re still trying to sort out what the new normal is…my sense is that we will see more difficult times before we turn the corner."

i guess it's not a good time to invest in emerging markets huh?

and canada ....due to profligate spending by trudeau???.....key factor in inflation is government overspending